Icelander Birgir Ómarsson discovered disc golf while studying graphic design in the U.S. in the mid-1990s. When he got back home after a few years abroad, he wanted to play more. But there was a problem.

"I found out there was no disc golf course in Iceland," Ómarsson said. "Nobody was playing. Nobody had even heard of it."

After a few years of trying, Ómarsson convinced local authorities to fund a course of his invention a bit outside of Iceland's capital, Reykjavík. With his creation fairly close to the city that, including suburbs, is home to around 60% of Iceland's population, the first-time designer hoped his project would be an instant hit.

It wasn't.

But it was a small ember that helped ignite an Icelandic disc golf scene that is now one of the world's hottest.

Iceland Disc Golf by the Numbers

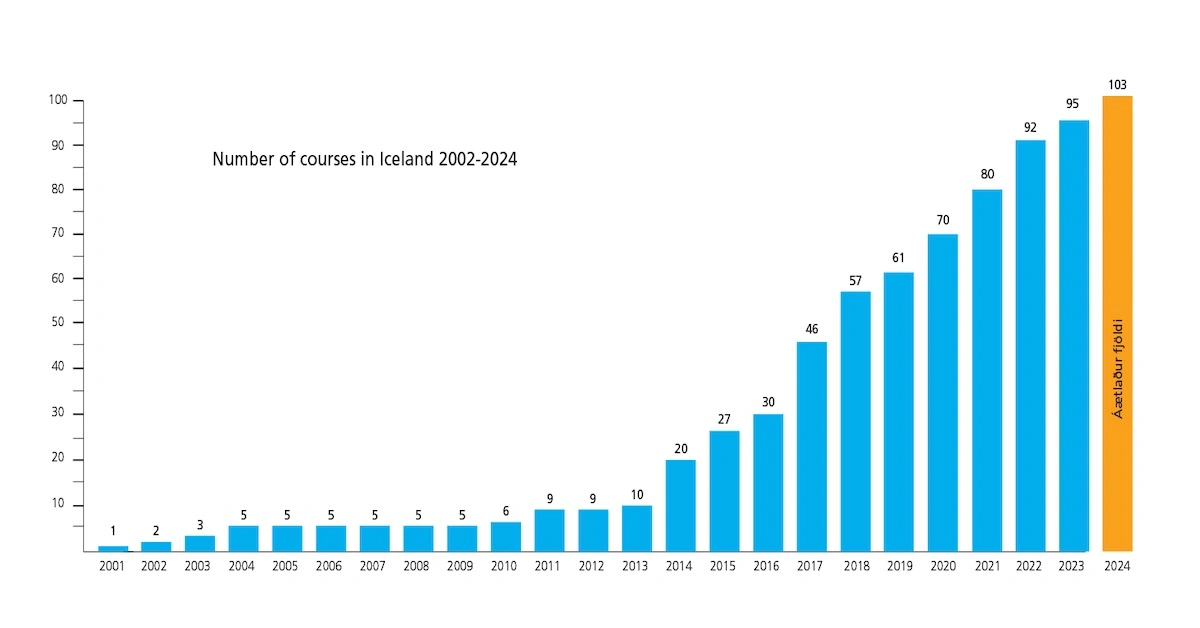

Though he recently retired from the role, Ómarsson spent 20 years as the head of the Íslenska frisbígolfsambandið (Iceland Disc Golf Association). During that time he witnessed disc golf in his homeland go from completely unknown to a common hobby.

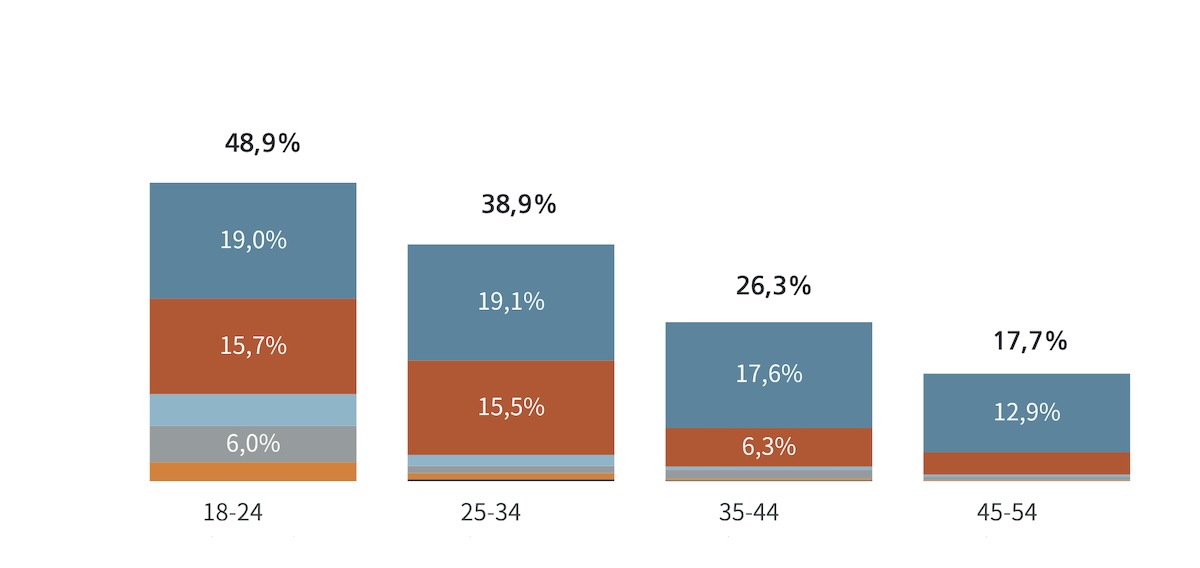

Studies conducted by Gallup concluded that in 2023 around 20% of Iceland's population of just over 380,000 had played at least one round that year. For people ages 18-24, that percentage went up to 48.9%. That means nearly one out of every two 18-24-year-olds in Iceland hasn't just heard of disc golf but actually went out for a round last year. People 25-34-years-old weren't far behind that impressive mark, with 38.9% having thrown a round in 2023.

There are two big reasons for these impressive numbers: Disc golf's pandemic popularity boost and the easy access to disc golf nearly all Icelanders enjoy.

"When the pandemic came, disc golf bloomed all of sudden," said Magnús Freyr Kristjánsson, an administrator in the Frisbígolffélag Reykjavíkur (Reykjavïk Disc Golf Association). "It also became one of the more popular things to do because you weren't allowed to do anything else."

Rounds scored with UDisc back up Kristjánsson's perception of the sport's rapid growth.

There were around just 17,000 rounds recorded with UDisc in Iceland in 2019, the year before the pandemic caused major shutdowns worldwide. After a surge to over 60,000 in both of the hardest pandemic years (2020-2021), the numbers predictably ebbed a bit – but to levels well above pre-pandemic tallies.

In 2023, there were nearly 50,000 Icelandic rounds scored with UDisc – nearly triple the 2019 total. Additionally, 250% more unique players utilized UDisc in 2023 as compared to 2019. Clearly, many Icelanders who found disc golf during the pandemic have continued playing.

Keep in mind that though UDisc is the most popular disc golf app, not everyone who plays a round uses it. The numbers we have related to rounds and unique players are just fractions of the full totals.

Though the pandemic boom was felt worldwide in the disc golf community, its effects were so significant in Iceland due to its impressive disc golf infrastructure. In 2022, Iceland had the highest disc golf course per capita rate of any fully independent nation in the world with, roughly, one publicly available disc golf course per 4,500 people. For comparison, the U.S.A. has about one course per 33,000 people. Even disc-golf-crazed Finland lags a bit behind Iceland with around one course per 5,200 people. In our recent Disc Golf Health Index, Iceland ranked sixth globally in disc golf availability, which is a metric assessing populations' ease of accessing a disc golf course.

Essentially, when other entertainment suddenly disappeared, most Icelanders had a disc golf course nearby to fill the void. And when the other entertainment came back, those courses were convenient (and good) enough to draw many people back to them even when they had other options.

Learning the Hard Way to Make Things Easy

So how, within just 20 years, did Iceland go from having a lone course that almost no one played to being a disc golf hot spot where most citizens have a place to play a few minutes away? According to Ómarsson, it took learning an important lesson – one anyone trying to build a disc golf community should take to heart.

"The first courses I built were too difficult, and it didn't catch on," Ómarsson said. "Making easier courses drives in more people."

For the first 10 years that Ómarsson promoted disc golf in Iceland, he created the sorts of courses he, an experienced player, enjoyed most. However, the majority of people he took to play them didn't have much fun. A now wiser Ómarsson knows why.

"If you go and try a new sport that's something you've never tried before like axe throwing, and it's so hard that you never hit the target, you have no desire to go back," Ómarsson explained. "But if you go and think, 'Hm, I'm pretty good at this,' you probably want to go back."

The first time he really understood this was after the installation of Klambratún disc golf course near the heart of Reykjavík in 2011. With holes averaging 48 meters/158 feet, it quickly became one of Iceland's most played courses.

"We had a park in the middle of Reykjavík, and it was the first course lots of people could see," Ómarsson said. "It was the first easy one we put up. We actually thought it was too easy, but everything started to roll on after that course. Making an easy course – almost like a putting course – is the way to go."

More evidence for the power of short disc golf courses came from Iceland's fourth-largest city, Akureyri, which is near the long, hard Akureyri - Hamrar disc golf course. Though Ómarsson believes it's one of Iceland's best courses, Hamrar saw sparse use over its first decade. That changed once a short course near the city's center, Hamarkotstún, was installed.

"As soon as we put in the shorter course, we could see that more people started playing the more difficult one," Ómarsson said. "You need the easier one to get people going. As soon as they've played it for a few months, they look for the more difficult one."

According to Kristjánsson, the Reykjavík club administrator, the clear synergy between easier courses and harder ones has made it the norm in Iceland to install a beginner-friendly course next to any new facility aimed at experienced players. He can also personally attest to how the strategy has paid off and helped give new players a better first impression of the sport.

"At our home course Grafarholt, we get so many families and so many beginners coming there, and all they want to do is throw the long teepads, but pretty soon they figure out, 'Okay, this is quite hard,'" Kristjánsson said. "It pushes people away sometimes; people get discouraged. But then it's really nice to step in and say, 'Hey, you can play a course just behind that tree over there that's nine holes, really short, and really fun.'"

Who Builds Iceland's Disc Golf Courses?

For many years after Ómarsson started his crusade to build a disc golf community in Iceland, getting funding and permission to build courses was an uphill battle. As in most places, disc golf in Iceland is largely funded by local governments, and competition for public funds is fierce.

But years of pitching the sport made Ómarsson increasingly proficient and confident, and he said the process became "easier and easier." That was especially true after the success of Klambratún. On one hand, it showed that disc golf could be popular and played safely in a park near the center of the country's largest population hub. On the other, it taught leaders in Iceland's disc golf community how to create courses that would attract constant traffic, and higher play counts meant a strong argument that disc golf courses were boosting Lýðheilsa, or "public health."

"Disc golf gets people of all ages to go out and exercise, meet other people, and have fun," Ómarsson said. "We are able to drag young people away from video games and Netflix and go out to do healthy things. This is the most important selling point."

As more courses went in around the country, more communities were interested in having their own or adding to their existing offerings. Kristjánsson said that nowadays in the Reykjavík area, local officials typically contact the disc golf association with requests for courses rather than the club starting conversations about them.

"Over the years, we've established a really good relationship with the city of Reykjavík," Kristjánsson said. "So let's say there's a town sector, and they want to have a disc golf course made in their area. They contact the city, and the city contacts us. We go and create the course and maintain it, and the city basically pays us to do it all. So that's how we fund all of our operations."

But there's not a never-ending cash flow for disc golf, and no one is making money off the course building projects.

"Most of the work people do is voluntary so the money can go into the club and we can maintain the courses," Kristjánsson explained. "We have to maintain the courses ourselves, pay the contractors to make tee pads, and so on."

Along with course maintenance, the Reykjavík club also runs multiple events for youth and beginners throughout the year. Keeping track of attendance for these events along with stats showing steady traffic at public courses is an important task. Such data is the main way that local decision-makers assess whether disc golf's impact on the community justifies continued public funding.

A Special Course for a Special Milestone

The newest course in Iceland's repertoire is Ljósafossvöllur, an Ómarsson design situated about an hour east of Reykjavík that opened in the spring of 2024. The project was special in many ways. For one, it was the most well-funded disc golf undertaking in the country's history with 20 million Icelandic Króna (€134,000/$146,000 USD) behind it.

"That's way more than we ever got for any other course," Ómarsson said.

The reason more funds were available is that the course-building effort wasn't backed by a local government but Iceland's national power company, Landsvirkjun. They had previously been maintaining a free, public traditional golf course near one of their hydroelectric power plants, but Ómarsson, who regularly plays traditional golf with his wife, said that was it wasn't high quality.

"There was a golf course there that was not a good one, so I got the idea that maybe they'd want to look into changing it," Ómarsson said.

He sent the company a letter with the idea to transform their golf course into a disc golf course five years ago. He got a meeting, but there was limited interest. Still, he continued to follow up, and he noticed them slowly opening to the idea.

"Then last winter I got a call saying they wanted to go for it," Ómarsson said.

Guðmundur Finnbogason, a community and nature project manager with Landsvirkjun, explained why the organization decided to make the switch.

"After operating a traditional golf course for over 20 years, we felt it was time for a change," Finnbogason said. "The usage of our course had been dropping and we saw the potential in disc golf. Birgir [Ómarsson] had floated the idea some years ago and we felt that it would be beneficial for us and the community to change from traditional golf to disc golf. We also like the simplicity of the sport and its accessibility for people and how it seems to engage a wider age group than the traditional golf."

The project's sudden approval and large budget was perfectly timed. Ljósafossvöllur wouldn't be just any course, but the country's 100th when non-public courses (owned by, for example, health institutions and exclusive resorts) were taken into account. To honor that milestone, Ómarsson set out to create a true destination that would thrill Iceland's disc golf community.

"This is the nicest course we've ever done," Ómarsson asserted.

The handsome wood-framed tee pads that each feature a sturdy bench are sure to be the first parts of the course to capture people's eyes. And repeat visitors will notice that the course alwas looks pristine as Landvirkjun has the equipment and resources to maintain the area constantly and consistently. Finnbogason told us that visitors have already noticed the course is a cut above the country's other offerings and have expressed their gratitude and wonder at seeing a disc golf course made and maintained at such a high standard.

"I think that what has surprised me the most is how well it has been received in the disc golfing community," Finnbogason said. "I was very happy when the players in the first tournament described the course as a gamechanger. We were hoping to do a very good job, but I was not expecting it to be moving the sport up a level or two in Iceland. This was a very happy surprise."

Along with high level upkeep and infrastructure, something more subtle stands out at Ljósafossvöllur, too. When you look over the layout, you'll notice the holes aren't the monsters you might expect when someone tries to build a marquee experience. That decision was made very deliberately by Ómarsson, who has learned the value of courses that appeal to a wide range of disc golfers.

"We have like 55,000 people playing disc golf in Iceland and 300 who are competing," Ómarsson said. "I told the association that I was making a course for the 54,700, not the 300."

The strategy has worked, too. A counter that Landsvirkjun installed last year before the conversion shows that the disc golf course generated more traffic in its first two weeks than the golf course did in all of 2023.

"We are extremely happy with the outcome and have seen it being used very well in its first month," Finnbogason said. "We are very happy with our decision to make the change."

These are outcomes that the Ómarsson of 20 years ago could likely never have imagined and that shows how Iceland's strategy of creating welcoming disc golf courses is boosting the sport's popularity and making it appealing to a wide range of people.

"The field of players in Iceland is so broad," Kristjánsson said. "You have people of every age playing together, every ethnicity, every background. Every physical status as well – we have really tough athletes and regular Joes. That plays a big part in why it seems so open and it is so open."