All data gathered and analyzed by Christopher Loan. Text by Alex Williamson.

At 2018’s Pärnu Open in Pärnu, Estonia, something almost freakish happened. A then 1042-rated Eagle McMahon shot a round that was initially rated 955 (later changed to 956 in the official PDGA scorebooks)—not far off from 100 points below his rating.

In post-tournament comments to Ultiworld Disc Golf , McMahon expressed incredulity at that number, saying, “Right off the bat, I wanna just tell you that the ratings feel like they’re a good 35-40 points off...it said 955 [for the second round], but in reality, it felt more like 990.”

You might be thinking, “So what? A high-level player played a bad round and complained about ratings—not surprised.” But McMahon's comments to UWDG relate to a common belief in Europe: In Estonia, ratings are lower than they should be. Adding more fuel to the fire of this suspicion is how in this year’s Estonian Open a 1049-rated Ricky Wysocki shot a 999-rated round and the 1035-rated James Conrad finished his tournament with a 961 effort.

Other evidence shows itself in how Estonians often outperform their ratings in other countries. Just this year at the European Open in Finland, Estonian Albert Tamm—rated 1004 at the time—earned a tied third place by averaging 1044 over four rounds, putting him on the podium with the three highest-rated players in the world: Paul McBeth, Wysocki, and McMahon. Fellow Estonian Kristin Tattar has only played three of her 15 PDGA-rated events in Estonia since going to the U.S. for Worlds in September 2018. Her rating has risen from 926 at that time to 956 as of the last update.

Though there is clearly a lot of anecdotal evidence that something may be up with Estonian ratings, we wanted to see if a close look at hard data supported this idea, too. We took a deep dive into the ratings at the 2017 and 2019 Estonian Open with this goal in mind, and below you can learn what we found out.

The Theory and How We Tested It, in Brief

Hypothesis: Rounds played in Estonia (i.e., with a majority of Estonian participants) produce lower ratings than they would had those same rounds been played elsewhere. When highly-rated foreign players come to play there, it should result in most Estonians receiving higher ratings than normal and just the opposite for foreign players.

Where the Numbers Came From: We examined two events in Estonia with an unusually high level of foreign-player attendance: the 2017 and 2019 Estonian Opens (there was no Estonian Open in 2018).

Placing Players: The "Location" indicated on each player's PDGA profile was used to group players by the country they likely most often played PDGA tournaments in. There were enough players from Estonia and Finland that they warranted having their own groups while players from all other countries had to be grouped into an "Other" category for the numbers to have much meaning.

The Math: We averaged the round ratings of all rated PDGA members at the tournaments and then found the difference between their rating at the time and that average.

For example, a player named Evgeni Smirnov played rounds rated 985, 994, and 985 at the 2019 Estonian Open. That averages to 988. His rating at the time was 946.

988 (the round rating average) - 946 (his rating at the time) = +42

Smirnov's location is listed as "Estonia" in his profile, so that +42 was added to the data set for, you guessed it, Estonia. This process was done with all individuals who completed the tournaments and had a PDGA rating. The resulting numbers were averaged together for each location group (again, Estonia, Finland, and Other) to find out whether players in those groups generally did better or worse than their ratings at the time.

The Results

We won't tease you. Here's what the numbers came out to:

| Country | # of Players | Average Rating Difference | Max. Positive Difference | Max. Negative Difference |

| Estonia | 125 | +8.67 | +67.33 | -46.67 |

| Finland | 75 | +.09 | +60.67 | -62.67 |

| Other | 44 | -15.01 | +33.67 | -97.00* |

*If the -97, an outlier, is removed from the data set, the Average Rating Difference for the Other group is -13.16.

As the chart shows, at the two Estonian tournaments with an abnormally high level of foreign attendance we examined, Estonians on the whole averaged almost nine points above their ratings at the time. Finns' ratings stayed about the same. Other foreigners? They had a tough go of it, on average playing 15 points below their ratings.

Having high numbers of non-Estonian players attend a tournament seems to have increased the Estonian's ratings on average while negatively affecting non-Estonians (other than Finns) on the whole. This suggests that if this had been a typical Estonian tournament with fewer foreign boosters, Estonians would have received lower ratings for rounds of the same score. In other words, the hypothesis seems to be correct.

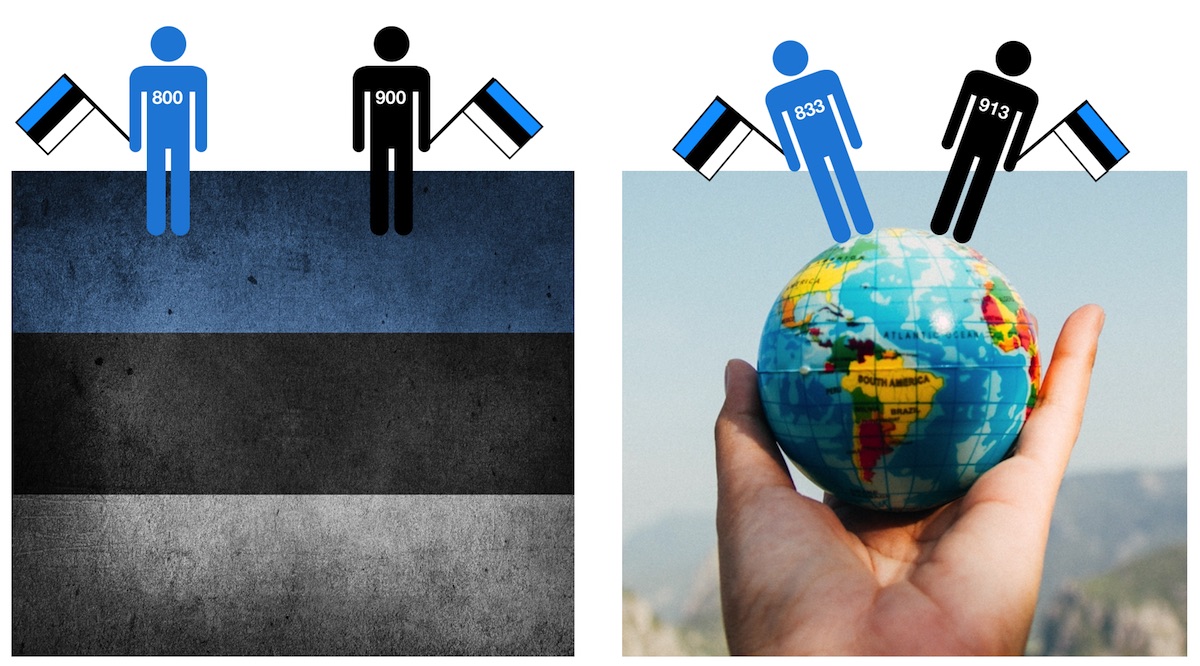

One other interesting point is that the positive impact of the foreign influx of players increased more for Estonian players as their ratings decreased. For example, the data predicts the following impacts for 800, 900, and 1000-rated Estonian players when they compete in tournaments with fields like the Estonian Opens of 2017 and 2019:

An 800-rated Estonian player competing in the Open division: ~ +33 impact

A 900-rated Estonian player competing in the Open division: ~ +13 impact

A 1000-rated Estonian player competing in the Open division: ~ -7 impact

If you're wondering what happened with the 1000-rated players, one possible theory is that the higher-rated Estonian players often play outside of Estonia, so their ratings are more like those of foreign players. That means they'd be more likely to score lower ratings when playing in their home country, just like those in the "Other" category. Again, this is only a possibility and we would have to do more research to prove it.

Final Notes

The ratings situation in Estonia doesn't show that the PDGA rating system there is wrong. This is likely what happened: Years ago, several Estonians began competing and probably set their ratings at low values because they were new to disc golf. They became Estonian propagators—players who are used to determine other players’ ratings (see PDGA website for more info). Those propagators and the field increased in skill at very similar paces, meaning the ratings based on these propagators were a "moving target" for anyone who wanted to increase their rating but didn't travel internationally. With Estonia being one of the fastest-growing disc golf hubs in the world, that means there were a lot of Estonians getting their first ratings and becoming propagators under these conditions.

Essentially, the cure to the Estonian ratings problem is exactly what Estonians have begun doing in recent years. Most importantly, many Estonians, from highly rated players like Kristin Tattar, Albert Tamm, and Silver Lätt to large numbers of amateur players, have been playing a lot outside of the country. When they've returned to Estonia, their ratings earned in places without the "moving target" problem have been helping to gradually establish better ratings. Big tournaments with international fields like the Estonian Open also help bring Estonian ratings closer to the international norm, and Estonian tournament directors have tried to increase the number of such events in recent years. For example, the country has hosted six A-tiers in its history despite its first PDGA-sanctioned event happening less than 10 years ago. *

We'd like to end by saying there are a lot more charts and details we didn't include in this piece. If you have a question or think of something we didn't consider, contact us at [email protected].

*A previous version of this article emphasized only the impact of large tournaments and Estonian pros' travel. It has been altered include the effects of traveling amateur players, as well.