While we were interviewing Allen Risley, creator of the Professional Disc Golf Association’s (PDGA) first course directory, for a recent article, he told an interesting anecdote. In a gallery at the finals of a big event, Risley was walking and chatting with “Steady” Ed Headrick, the man known as the father of disc golf and the inventor of the Disc Golf Pole Hole. The Pole Hole is the first ancestor of today’s disc golf baskets.

Risley said at one point their conversation turned to the logic behind Headrick’s original design for his disc golf target.

“He was trying to come up with something that mimicked if you were playing catch with another person,” Risley said. "The best way to make sure the other person would catch the Frisbee was if you hit them right in the stomach.”

Risley reported Headrick adding another interesting tidbit, too.

“The chains didn’t always catch perfectly, and his explanation for that was if you putt too hard, you’re going to hurt your friend,” Risley said. “He designed the chains so that you’d have to have a certain amount of touch on your putt.”

These compelling revelations about such an integral piece of disc golf equipment made us want to delve more deeply into the history of baskets generally. To do this, we reached out to Scott Keasey, General Manager at DGA, the company Headrick created shortly before founding the PDGA. Keasey was personally hired by Headrick in 2001.

DGA is still a top producer of chain disc golf baskets, with various targets in its Mach Series catching discs on courses across the world. Through talking with Keasey we learned how the company Headrick founded has taken his original idea and adapted it to both fit and shape how our ever-evolving sport is played.

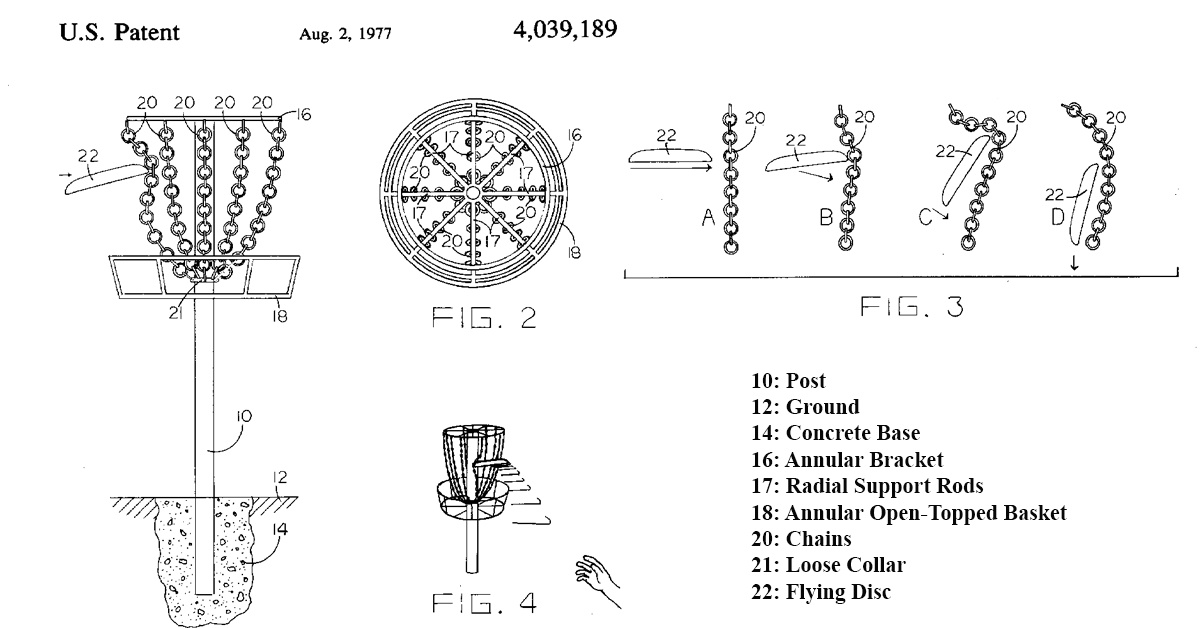

The Prototype “Flying Disc Entrapment Device”

The original patent filed by Headrick for the “Flying Disc Entrapment Device”

“What became the Pole Hole—the Mach I—was not where [Headrick] started,” explained Keasey. “He definitely played around with some things. He knew they needed some sort of device that would stop a disc. They obviously played around with posts and other methods, but it was one of those things where it was kind of subjective.”

Subjective in that players hitting poles would often argue about if a disc touched the target. Imagine, for example, the heated discussion that could occur at a tournament about whether a disc grazed the side of a pole above a certain height when all players were 250 feet/76 meters away.

The solution to this issue came to Headrick while tinkering in his garage.

“So the story I’ve heard was, as Headrick was playing around with different objects to deaden the disc and slow it down, he was in his garage, and he had some chain hanging from the rafters,” Keasey said. “He threw a Frisbee at it, and the way that the chain wrapped around the disc was his ‘aha’ moment.”

Headrick, along with his son Ken, tried different designs but ultimately decided upon the circular design seen in the patent.

“He welded all the original baskets himself, him and his son Ken, and some of those baskets are still in use today,” said Keasey. “He never kept any of them. Headrick was always looking forward—never looking back or thinking about the history. A lot of true entrepreneurs are like that.”

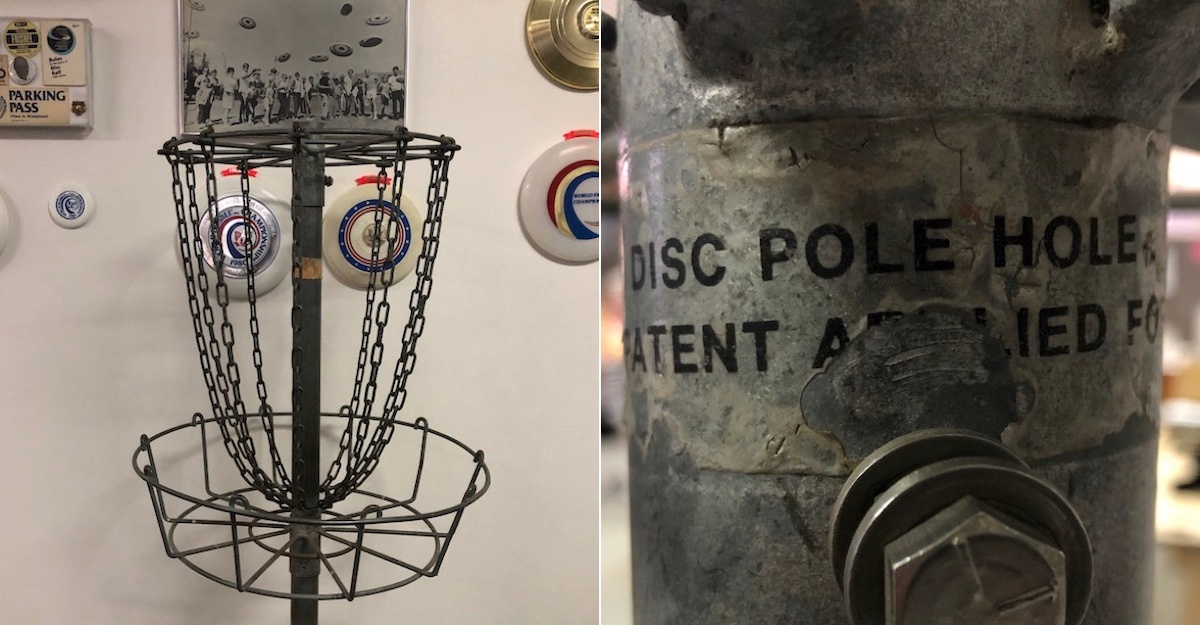

Perhaps a little more sentimental, Keasey has managed to find one of those early models, and he keeps it in his office.

“The one I have here in the shop has a sticker that says, ‘Patent Applied For,’ and I can tell by the way it was built and the number of chains, it was one of the early models,” Keasey said. “The traditional Mach I’s were 12-chain baskets, but the prototypes before that had only 10 chains. And there are not a ton of those around. This basket was floating around for years getting passed to various different people around southern California before it made its way back to DGA. If you look at it today, there’s no way you’d think it was 40-plus years old.”

Creating a high-quality and long-lasting product was hugely important to Headrick, something his original baskets still being in use are a testament to. Along with personal welding, Headrick utilized the method of hot-dipped galvanizing, during which the steel frame and chains of the basket are dipped in molten zinc to assure corrosion-resistance and durability.

“It’s obvious when you're thinking of something that has to be out in a park setting—which was his vision—it has to be something that is very durable,” said Keasey. “Hot dipped galvanizing was another huge deal for the construction of these early baskets. It really stands the test of time and the weather elements that can be thrown at it. That was another huge mark for the development of the sport.”

One of the biggest steps taken in disc golf history happened after Headrick had finished his designs and fabricated enough Mach I baskets to install them at Oak Grove Park by his home at La Cañada, California. This created the first-ever disc golf course with permanent chain baskets.

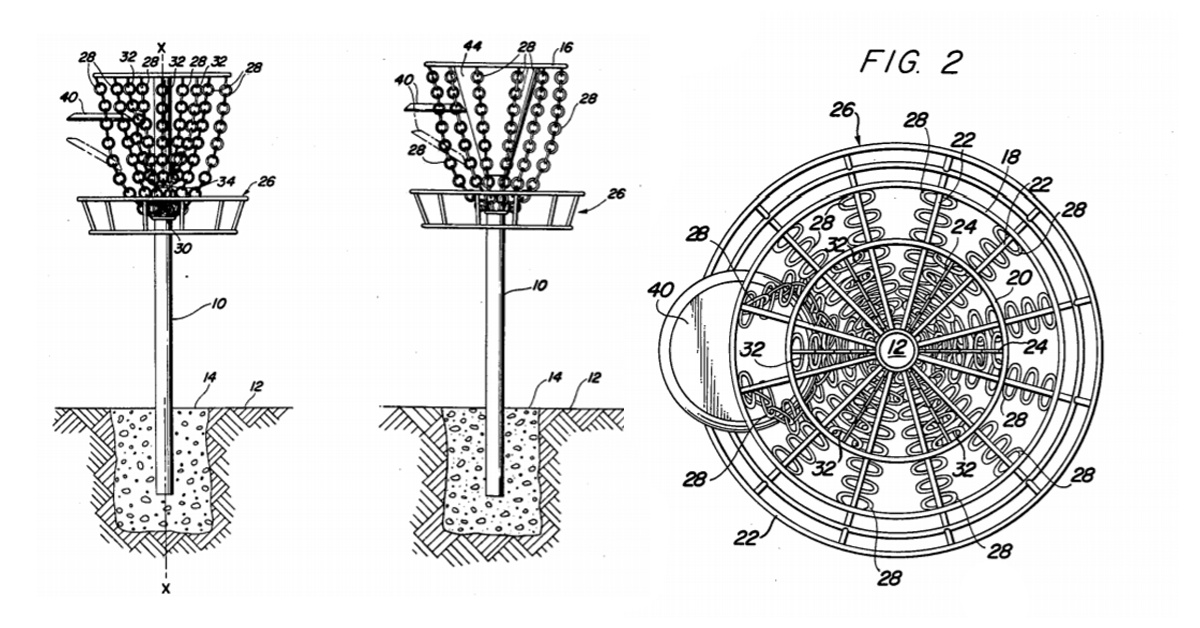

The First Evolution: Mach II & The Inner Ring of Chains

Mach I’s were a huge success and their spread marked the beginning of disc golf’s transition from object courses to what we know today. However, Headrick did notice some aspects of his design that needed improving. As disc weight increased and putters became heavier and capable of higher speeds, he felt the number of chains needed to increase. In his second patent, he addressed this concern.

“The device described in the [Mach I] patent, while functioning very satisfactorily with large, lightweight discs (e.g., 23 centimeters or more in diameter and about 100 grams in weight) does not always capture discs which are smaller and heavier,” wrote Headrick.

However, instead of just adding more chains along a single plane, Headrick thought of a more advanced solution.

“These [Mach I] baskets were originally designed to catch Frisbees,” Keasey said. “There weren’t a ton of chains in them, but Frisbees weren’t super heavy, so it did the trick pretty well. Once he developed the Mach II, the next innovation was multiple rows of chains. There was not just an outer row of chains; it went to an inner and outer row, for which he was also able to receive a patent.”

This alteration indeed improved the basket’s ability to catch discs, and it’s no surprise that other companies sought to replicate and improve on it.

“From there it’s been the ‘Chain Race’ for years—people kept wanting to add more chains and I think there's a diminishing return,” explained Keasey. “You can't keep throwing a ton of chains on there because too many will start acting like a wall and will reject discs. There have been a number of chain designs out there that connect chain on the outside in one single outer layer, and in our testing, it's not an improvement—it actually makes the experience worse. It’s been a balancing act, we’ve found.”

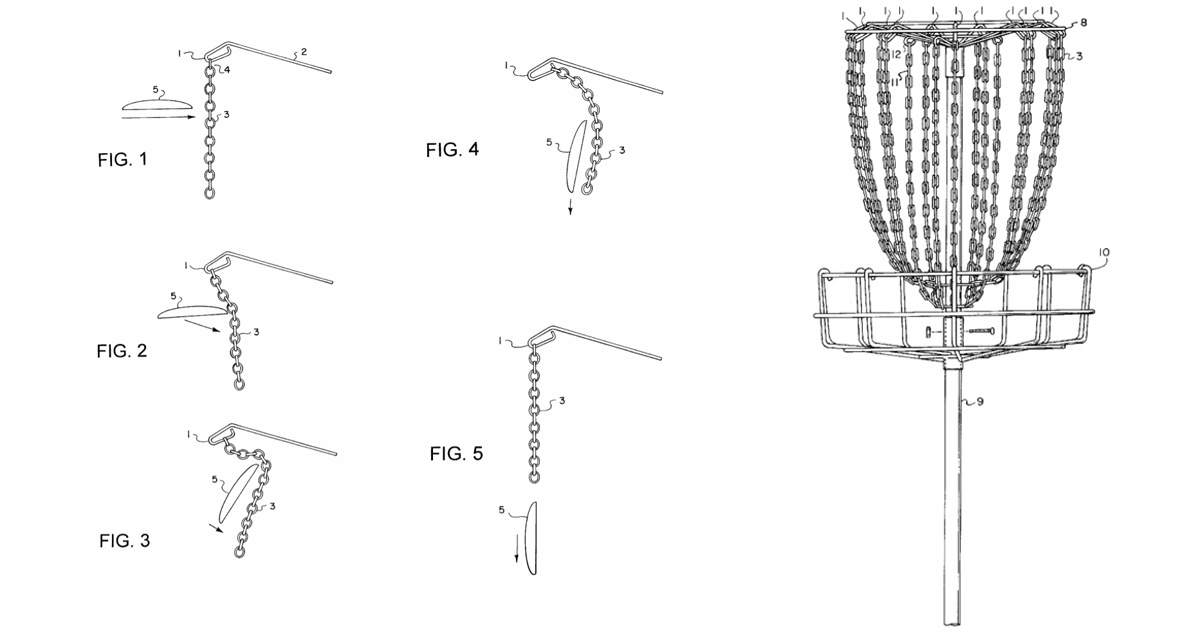

Further Improving the Basket: Mach III and Beyond

“I think the Mach III is probably one of the most iconic baskets ever made,” said Keasey. “It came out right when the sport was really taking off and there were probably Mach IIIs on more courses than any other basket.”

The Mach III continued Headrick’s search for the perfect disc golf target, experimenting with the length and diameter of the inner ring of chains. The Mach III patent included a bottom ring that was nearly the same diameter as the top ring, creating a reverse parabolic shape that, while eye-catching, wasn’t ideal.

“He quickly realized that wasn’t the best design,” Keasey said. “It wasn’t catching discs very well, so he moved to the more traditional ring size for the inner ring.”

Along with this tweak, the Mach III also raised the total number of chains to 24 and made DGA's now-iconic round number plate on the top of its baskets a default feature. The patent for this basket was granted in December of 1988 and was the gold standard of DGA’s baskets until the Mach V was released in 1999.

“When Ed released the Mach V, the innovation there was the sliding link,” Keasey said. “On the Mach V, the basic idea was allowing the movement of that outside strand of chain—give it a little bit of movement so that the disc can really penetrate and slow the momentum down instead of it hitting firm and potentially bouncing out. That was a big development that we continue to use on our baskets.”

Along with the sliding link, a third row of chain was added, but the total was kept to 24.

The Baskets of Today

Ed Headrick passed away in 2002, leaving Keasey to oversee basket evolution at DGA. Over the years, Keasey and DGA continued tinkering with the design of disc golf baskets and released the Mach X (pronounced "ex," not "10") in 2013. It combined many of the tried-and-true technologies of previous generations with new innovations.

The Mach X has a whopping 40 strands of chain in a unique configuration: The basket has reflex and recoil chains to catch and direct putts downward, a unified chain design that consolidates each strand to one single ring at the bottom, and 16 inner cross-connecting chains which in part give the basket its signature look.

“When we came out with the Mach X, it was the same time you started seeing a lot of those Sportscenter Top 10 Ace’s, and it seemed like a fair number of those were on Mach Xs,” Keasey said. “It seemed like if you got anything close to that chain, it was just gobbling it up.”

When discussing the release of the Mach X and Headrick’s posthumous influence on its innovation and design, Keasey noted Headrick’s importance.

“It’s always interesting when you develop something, you dream something up, and you put it out there and you're never quite sure how people are gonna react to it,” said Keasey. “Ed was the same way—you spend so much time developing and working on it you don't spend much time thinking about how it's gonna be received. You've done your research on it, and hopefully it does well. I think I gleaned some of that from Ed.”

The Mach X is highly regarded and now found on many championship-level courses across the globe. But DGA hasn't stopped innovating.

Just last year, they released the Mach VII. In appearance and chain number (28), it's more akin to the Mach 5 than the Mach X. However, it does have a new chain configuration that "catches remarkably," according to Keasey. It's also the first basket to move the visibility band inside the chains, which Keasey said gives it a unique look and could help players concentrate more on the chains and less on the band.

More Links in the Chain

Though at first glance today’s disc golf basket may share some visual similarities with Headrick’s first Pole Hole, innovations small and big made over the decades by Headrick, Keasey, and DGA helped create the durable and more reliable targets we have today. We couldn't be more thankful to Keasey for taking the time to help us learn more about this sector of disc golf history.

Of course, there are also more stories to tell about disc golf target evolution, and we hope to be able to bring others to you in the future. If you have any interesting information on this subject, feel free to get in touch with Release Point's editor, Alex Williamson, at [email protected].